Best practices in pricing for wholesaler-distributors

Pricing has become a hot topic with distributors over the past few years, and for good reason. It’s not uncommon for a successful initiative to improve gross margins by two points or more. Because this improvement drops straight to the bottom line, the profit impact can be huge. Several clients have told me that pricing projects literally saved their companies during the Great Recession.

Of course, nothing this good ever comes easy or without risk. In this blog post, I’ll summarize some of the most important lessons that our consulting firm has learned about effective pricing in wholesale distribution.

The first lesson: Start by thinking strategically, taking a long-term, market perspective rather than just an opportunistic, profit-and-loss view. If you are starting at how much more you can squeeze out of unsuspecting customers, you will face a far higher risk of customer backlash. You are also less likely to realize sustained margin improvements.

Distributors generally rely on what is technically known as a customer intimacy strategy. This means that success rests on long-standing relationships and maximizing the lifetime value of customers. A customer’s aggregate, ongoing revenue stream is more important than the profit from any particular order. (As an aside, this dynamic is different from other industries such as airlines or home builders, where maximizing each transaction is the right approach).

Fundamentally, pricing strategy should be based on capturing the value that you deliver; it’s not about deceiving or tricking customers. Relying on ignorance or habit is not a viable approach, especially in the information-everywhere-social-media age in which we live today. Sure, you can probably sneak in price increases on low-volume items and get away with it for a while. But at some point the changes will be recognized and you will have to be offering enough value to justify it. Pricing projects are notorious for showing major margin gains up front that melt away over time. The last thing you want is for a loyal customer to catch you “speeding.” You run the risk that a small-dollar pricing gain destroys the trust that you’ve built, leaving you with a suspicious customer who now examines every invoice with a magnifying glass.

With this mindset, pricing optimization is largely about finding the customers and situations for which you are not being paid market value for the services provided. You may be over-serving some of your customers, who would be willing to pay more to buy from you. But other customers may be all too happy to switch you out for a few pennies. Ultimately, more effective pricing requires that you can differentiate between the two scenarios.

It’s important to remember that “market value” is not what you think you’re worth, but what your customers think you’re worth. You may feel that superior technical knowledge at your counter or face-to-face field sales calls are really important. But if a customer chooses to buy from Amazon instead she is telling you loud and clear that these services are not worth a price premium.

A good way to discover where you are over-serving or underpricing customers is to search for patterns where similar customers get radically different prices. More likely than not, customers at the higher end are paying closer to market value while those at the lower end are being underpriced. Root cause analysis will often show that these situations are the result of giving sales reps too much discretion, too little guidance and/or insufficient information to make good decisions.

It’s difficult for most distributors to do effective external research on market pricing because their price levels tend to be customer-specific. While most industries may have a handful of price levels for a particular product, distributors may have hundreds or thousands, none of which are published. For this reason, pricing consultants and software companies typically rely on internal transactional data to find underpricing opportunities.

The assumption is that customers are typically less price sensitive on items that they buy infrequently or that make up a small portion of their total purchases. These methods have proven to be effective, but you should always remember that transactional characteristics are only proxies, or indicators, of customer sensitivity. There’s no rule that customers will always be less sensitive on C and D items than on A and B items, or that smaller or lower-profit customers will pay more. Customers don’t care about your pricing categories or how much they cost you to serve. They care about their overall cost for the product/service bundle that meets their minimum needs.

Before starting any major pricing initiative, develop a clear picture of the current state of your pricing. Create a simple pie chart showing the percentage of order lines priced using each of the available methods (e.g. standard column or matrix, customer contract, special project deal, vendor supported discount, sales rep override). Create a second chart showing the percentage of sales dollars broken out into these same categories. There’s a good chance that producing these charts will be eye-opening all by itself. We’ve often found that companies don’t have clean-enough data or even a systematic way of determining which method was actually used.

These pie charts ensure that you point your pricing efforts in the right direction. For example, it’s pointless to invest in updating all the pricing columns or matrices in your ERP system if these are overridden most of the time anyway.

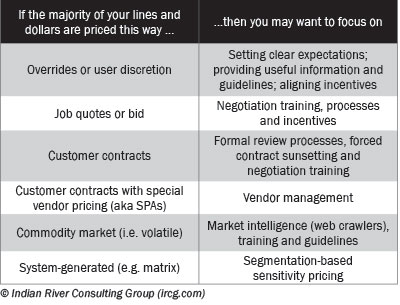

The following table summarizes the high-level implications of your pricing method breakdown:.

Class-leading distributors treat pricing as a process, not a one-time project. They assign pricing responsibility at the executive level; invest resources to continuously monitor and improve pricing realization; and have systematic feedback loops to objectively measure the impact of changes. We’ve found the best results when the pricing owner is in a product management or product marketing role. If measured on product profitability, she will be well-placed to make appropriate trade-offs between gross margin percentage (speed) and revenue volume (altitude). Sometimes lowering prices will actually generate more total gross margin dollars, not to mention give the sales reps competitive weapons to open doors.

If pricing responsibility falls to the financial side of the company, policies may be too strict or aggressive, leading to poor adoption with excessive overrides or exceptions. Because they don’t have daily customer interaction, internal accounting staff may be naïve about the level of competitive intensity or risk of customer alienation. On the other hand, giving the responsibility to the sales organization may lead to the opposite extreme: a timid implementation with loose rules that fade over time.

In fact, it’s common for a distributor’s sales force to be a far bigger impediment to improved profit through pricing initiatives than its customers. But this is just another reason to approach the opportunity strategically. If your sales team sees that you’ve done your homework and that the intention is for pricing to be consistent and fair, they will be far more receptive. Here’s a great reality check: Do a role play exercise with one of your reps in which you act like an aggrieved customer who has just received a price increase. If the sales rep can successfully explain a justification you’ve both done your jobs.

Give us a call today at 321-956-8617 to discuss this important topic or fill out our contact form.